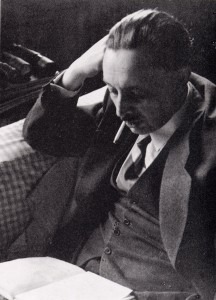

“Once upon a time there was a prince … ” educated, proud, Sicilian and at the same time a citizen of the world. Hard to say where the Prince of Lampedusa starts and where the Prince of Salina ends. For everyone The Gattopardo is the iconic novel that continues to fascinate generations of readers and whose footsteps are imprinted in our DNA. But the man, the writer and the traveler can be summarized in the single figure of the “Prince”? The question mark is a must when it comes to discern between the man and the literary character and even more when we try to find a key to understand an author known for a single great novel. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa is a complex figure that can not be read only in the light of his famous book or for his being a Sicilian. He was much more, and, through the exploration of his historical, geographical and biographical routes we will try to draw a portrait of the author, different from the typical baroque and inconsistent frames.

The result of this exploration will be the traits of a writer and a man with many polyphonic voices. Lampedusa, first of all. It is not useless to note that what for him was the starting point for many people today is a point of arrival, the goal of a hope. Lampedusa is an offshoot of Europe in the heart of the Mediterranean Sea, land border and port known for landings, drownings and trafficking of human lives from the coast of nearby Africa. The story changes but remains, despite the differences, the constant, immutable characteristics of human beings, the moods, the miseries, the need for a ground of certainty and, on the opposite side, the flow of change that eradicates and upsets.

For these and other mysterious reasons, for this mixture of ancient and modern, poetic and rational, anthropological and philosophical, Tomasi remains an author still able to meld different characteristics, generating viewpoints, influences and discussions among readers and critics.

His Gattopardo has become over the years much more than a successful novel and a popular film. It has become an icon, an inspiration for endless quotations. It has become a way of saying, the symbol of an era and a way of thinking, almost identifiable with a copyright, such as an aspirin or a coke. As it often happens, however, in literature and in life, in that long windy point oscillating that unites and divides, between the words and the truth, the man and the work, there is a beautiful stretch of beach. In the specific case of Tomasi, the waves in question are those between Scylla and Charybdis, between Sicily and the Continent, understood also as Europe.

As happened to another complex and multifaceted Sicilian author, Luigi Pirandello, Tomasi also travelled to the north. In five years of intense journey, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was able to get to know some of the major European capitals. He was looking for the authentic spirit of places and peoples, the true face to compare with that of his Mediterranean island. He discovered the beauty of Paris, and found himself particularly at ease in London, a city that he found full of bonhomie. But also explored the darker charm of Berlin. He visited museums, but was attracted also by the busy streets and tracks already made legendary by the great books of the past. He frequented fashionable salons but was attracted by everything, assimilating facts and voices with vivid curiosity. He traveled with a repertoire of quotations and wrote letters of lush fantasy in which he confirmed his thirst for knowledge.

Although he was much different from another imaginative storyteller like Gabriele D’Annunzio, he also wanted to give a spectacular image of himself. This insatiable verve found an effective synthesis in his “Travels in Europe. Correspondence 1925-1930 “. Tomasi di Lampedusa, shy, refined, passionate about comparative literature, gives the impression of traveling by choice, for fun and for inner enrichment, for the need to break away from the deep roots that nourish him and lock him at the same time. He travels for the desire to make its culture actually European. To be a man of the world, even before being a writer.

Duke of Palma di Montechiaro and Prince of Lampedusa, Giuseppe Tomasi was born in Palermo on December 23th 1896. He graduated in classic studies in Rome where he also attended the Faculty of Law, but did not graduate because he was called to arms. He was a soldier of the Italian army during the defeat of Caporetto and was taken prisoner by the Austrians. Then he experienced the horrors of war, the most raw and real, the violence that cancels the gap between noble class, bourgeois and the men of the people. A condition that makes clear and cruelly true the fragility of the human condition, the ferocity of time and history, but also the strength to keep close to a beauty that is the only source of survival of humanity.

Tomasi di Lampedusa was often a guest of his cousin, the poet Lucio Piccolo. Thanks to him, he had the opportunity to attend high-level literary circles, as in 1954 when he took part to a literary conference in San Pellegrino Terme where he met, among others, Eugenio Montale and Maria Bellonci.

Upon returning from that trip, like a volcano that reaches the ideal level of pressure, Tomasi began writing The Leopard, the romance of a lifetime, of many possible lifetimes. The novel will be completed two years later, in 1956.

His novel is defined as an example of ” poetry in prose”. Because the poetic form has the capability to bring together and synthesize contradictory instances and feelings through the coincidence of opposites. The link to the past was a mirror to talk about the present and the future.

And probably, it was precisely this strange ambivalence between modern and old that caused the rejection of the book by many publishing houses it had been presented to. Rejected first by Mondadori and then by Einaudi in both cases by Vittorini, the novel was discovered and enjoyed by Bassani who proposed it to Feltrinelli who finally published it. And it was a resounding success. Unfortunately Tomasi di Lampedusa was already dead in bitterness and discouragement of not being able to see his work published. The Gattopardo had a quite unique destiny. Tomasi di Lampedusa was an outsider for the official literary world, which remained in the habit of rejecting the new, no matter the value and origin. But here and now, after the affair came to an end with the resounding success of the book which the author could not benefit in life, we can try to capture elements of the work and of the writer in a wider perspective. Tomasi di Lampedusa was certainly, to quote Montale, "the author of just one book ", but in this volume he has enclosed the whole of his European experience assimilated without preconceptions, with genuine passion. The Gattopardo is the result of a work of accumulation of notes and sensations lasted years, written with a form of expression that can combine the metaphorical synthesis of poetry and the documentary accuracy of the historical novel. The novel was both classic and forward-looking. It was ahead of its time, while talking about an era that had passed. Placed in this border land, the book needed a slow assimilation before being perceived by critics as a work of absolute value. The rest is history: of literature and cinematography. The Gattopardo, the Leopard, is the result of a graft: the European culture implanted on the ancient branches of Sicily, the north wind on the silences and the air stopped on too many centuries of inaction, as stressed the Prince of Salina in a famous passage: “Sleep, my dear Chevalley, sleep, that is what Sicilians want, and they will always hate anyone who tries to wake them even in order to bring them the most beautiful gifts” The book transcends the novel. The book is so rich in content to offer multiple perspectives: historical, philosophical, psychological, social, geo-political. But it is also a brave book, in which the look on the cultural legacies that have created the humus of mafia is absolutely sincere.

As in geological layers, this book goes far beyond the historical fresco, over the story, over the characters, the places, the costumes. In this context we can read the quotation for excellence, the one that stands on the novel and identifies it immediately: If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change. The Leopard tells us about the the doubts and the hopes of men and women of their time in front of a changing world that redefines values and styles. It tells how men face the change and how identities, histories and culture face the time.

Considering The Leopard a conservative book is for the most a short-sighted attitude: there is, alive and present, the historical awareness of the evils of Sicily. Seen not as microcosm in itself but as a symbol of an ancient way of living and thinking forced to look with different eyes to new times. There is a form of loud and clear social criticism in the book. The love for his land is not blind.

The characters of the novel sublimely wrapped in humanity, are chiseled in their ambivalence. This probably is the key word: ambivalence. The novel is at a crucial hub of Italian history and beyond: the moment when you realize that a certain society, a certain way of life and thought is intended to be outmoded, by history. Tomasi, however, does not live with a passive and resigned attitude. He is not an uncritical cantor of the past, and does not unconditionally enhances the old days, “les neiges d'antan”. The core of his thought is the will to bring in the new times what is best in tradition and authentic bond of the land of origin. It is also thanks to Tomasi di Lampedusa if Italians are aware of their great gift and their condemnation. The distant, melancholy and nostalgic look of the Prince of Salina on the one hand, the narrative style of the Author-Prince, must not mislead. The book screams out a timeless truth, reveals the illusions, the traps and mirages of rapid changes, the dangers of cunning and turncoats, teaches us to look beyond the surface, beyond the contingent things, in a perspective that Leibniz should call sub specie aeternitate. The Leopard is a work with a high educational and intergenerational value, because every era, as well as any man, is suspended between two extremes, one that changes at every moment, and a past that escapes, slips away, tending to become unrecognizable. We were the leopards, the lions, those who take our place will be jackals and sheep, and the whole lot of us - leopards, lions, jackals and sheep - will continue to think ourselves the salt of the earth. In this statement, within this tension, is perhaps the key to success and the timeless appeal of the book and its author: the meaning of human limits but also the desire to carve out with tenacity a space in the inscrutable drawing of time.

Ivano Mugnaini