Monte Stella: Variazioni sul tema del tempo e della realtà

in Luigi Fontanella

Il riferimento alle variazioni sul tema richiama immediatamente la musica. Un mio professore del liceo sosteneva che la musica è matematica. Un altro sosteneva che è illogica astrazione. Entrambe le affermazioni sono vere ed entrambe sono false. È qui che subentra la poesia. La sola in grado di accogliere in sé il vero e il falso, la realtà è ciò che va oltre, sopra, sotto, nei meandri, nelle vene sotterranee, al di là del confine e del limite.

Il recente libro di Luigi Fontanella, Monte Stella, parla di moltissime cose. Spazia, racconta, immagina, disegna e compone. Ma soprattutto gioca, con “orrore” ma anche con il gusto di addentrarsi dentro un dedalo di “cose buffe”, con il Tempo, operaio, capomastro e inesorabile padrone della palazzina eternamente in affitto e perennemente in costruzione che è la Vita.

Per parlare adeguatamente di un libro ricco e complesso come Monte Stella bisognerebbe essere amici del principale e possedere moltissimo del suo materiale da costruzione. Qui ed ora, in questo spazio telematico, ciò non è possibile. Ma abbiamo comunque a disposizione un modo semplice e bello per fregare il “capoccia”: comprare il libro e leggerlo, con la dovuta calma e la dovuta attenzione che si riservano a parole che sono il frutto di anni di scrittura, di ricordi e di vita vissuta.

Hic et nunc, possiamo esplorare, come in un immaginario volo di aliante, il Monte eponimo.

In primis, qualche chiarimento sul titolo, in apparenza sibillino, di questo articolo. Conosco Luigi Fontanella da alcuni anni e ogni tanto mi reco nella sua casa fiorentina per fare una chiacchierata di aggiornamento. Sarebbe elegante e assez maudit dire che beviamo litri di Chianti, invece spesso ci gustiamo ottima acqua, oppure, visto che arrivo sempre nel pomeriggio, un tè. Poco british, ma sempre tè. Durante le nostre chiacchierate parliamo non solo di idee astratte ma anche dei modi concreti, dell’aspetto “pratico” dello scrivere, che poi, a ben pensare, influisce molto sulla forma e sui contenuti. Fontanella mi ha rivelato che spesso scrive di notte, nel dormiveglia, e che per poter annotare rapidamente le idee utilizza un magnetofono. Ecco, credo che in questo oggetto, a metà strada tra modernità e tradizione, passione e riflessione, immediatezza e ragionamento rielaborato come materia onirica plasmabile, ci sia molto della poetica di Fontanella in generale e del libro di cui ci occupiamo ora in modo più specifico.

Faccio riferimento ad un’intervista rilasciata da Fontanella a Rodolfo Di Biasio per il magazine “America Oggi”. Nella risposta alla domanda iniziale, Fontanella cita il suo libro d’esordio, La verifica incerta, pubblicato nel 1972. La sua reazione al pensiero del lasso di tempo trascorso da quella prima pubblicazione è «stupore misto a incredulità e orrore». Entrano in scena, qui, gli altri due “oggetti” del titolo: il cronometro e la clessidra. Il primo è lo strumento atto ad un’inesorabile, scientifica misurazione. Un modo asettico di calcolare lo scorrere dei secondi che diventano meccanicamente anni e poi decenni. La clessidra invece è un marchingegno più semplice e più complesso, in ugual misura: è un concetto più che un oggetto. È talmente lento da concedere di inserire, assieme alla sabbia che scorre, anche il sapore del mare che si è vissuto, dei campi della gioventù, delle regole, delle trasgressioni, dei volti amati e odiati, delle persone affini e quelle da cui ci si è allontanati. La clessidra è un simbolo. Forse è la poesia: una misurazione volutamente, necessariamente umanizzata. L’opposto della precisione. È un tempo che, pur restando spietatamente “palazzinaro” e “usuraio”, si può rendere, tramite il gioco e il trucco delle metonimie, quasi umano, sostenibile, cantabile. Il quarto oggetto, non citato esplicitamente ma sempre presente, è un metronomo: la musica è un modo di muoversi nel tempo in modo più armonico, meno robotico. I riferimenti alla musica, diretti e indiretti, allusi o dichiarati come abbracci, sono numerosi e significativi. Si veda in particolare l’ultimo componimento del libro, “Il movimento dei rami” che Fontanella introduce in questo modo: «nato esattamente da alcune suggestioni derivate dall’ascolto di una composizione al pianoforte di Ezio Bosso: un musicista che ho scoperto sette anni fa. La sua immatura, recente scomparsa mi ha profondissimamente addolorato».

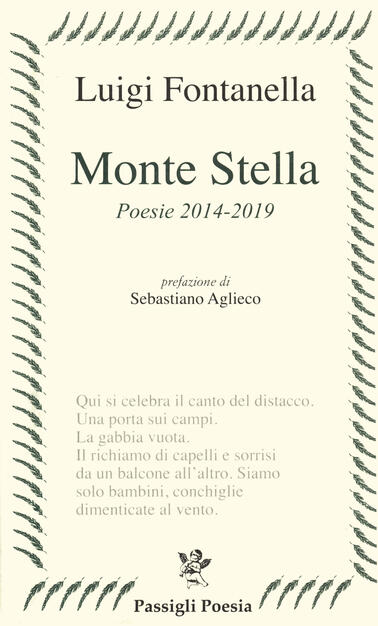

Su questo terreno ha luogo lo scontro, la battaglia decisiva: preso atto del lutto e del processo dell’invecchiamento (un’azione costante di aggressione a ciò che abbiamo di bello e di caro) resta da impostare una strategia, necessariamente autonoma e individuale, di difesa. Non è un caso forse che sulla copertina del libro campeggino, come uno stemma, versi essenziali: «Qui si celebra il canto del distacco. / Una porta sui campi. / La gabbia vuota. / Il richiamo di capelli e sorrisi / da un balcone all’altro / Siamo / solo bambini, conchiglie / dimenticate al vento».

Prima di tutto la celebrazione, la ritualità. Volere e sapere dare sostanza di emozione, nell’attimo e nel ricordo, ad ogni accadimento, anche quelli in apparenza minimi, conferendo loro una laica, sentitissima sacralità, è la prima barriera contro l’avanzare dell’oblio. Poi quell’esclamazione, lieve e possente, “siamo solo bambini”. Genera innanzitutto una ciclicità, un continuum tra infanzia e senescenza. E si sa, il cerchio non ha spazi vuoti, non consente al nemico di insinuarsi all’interno senza essere contrastato. C’è, inoltre, il richiamo all’aspetto ludico, del vivere e dello scrivere. È il contrario della sciatta approssimazione, questo va chiarito. Si tratta, al contrario, di quella deliberata volontà-necessita di guardare il lato oscuro della luna, l’umorismo pirandelliano, la salvifica autoironia di Svevo (che Fontanella ha studiato e assimilato a lungo e con cura), oppure la verve dissacrante dei surrealisti, a partire dall’amatissimo Breton, fino a raggiungere uno ad uno tutti i modelli e i compagni di viaggio ideali, Bontempelli, Artaud, Pessoa, Aleixandre, Landolfi, Rilke, Delfini, Campana, Corazzini, Calogero, Gatto, Savinio, Anna Maria Ortese e molti altri che non elenco ma che chi legge il libro ritroverà, nitidamente. Autori diversi tra loro eppure con un filo rosso che lo stesso Fontanella identifica nella loro ispirazione visionaria sostenuta però da esperienze forti e laceranti, di vita vissuta.

La vita vissuta contrapposta alla dimensione onirica. Anzi no, non contrapposta, semmai affiancata, sovrapposta, in un intreccio astratto e tuttavia carnale. La poesia recente di Fontanella è contraddistinta da questo fare bilanci “in fieri”. Già ne L’adolescenza e la notte l’autore ripercorre le strade dei ricordi e li conduce di fronte al presente consentendo loro di incontrarsi, guardandosi negli occhi.

Quella che nel libro precedente era una contrapposizione dialogica, un contrasto, qui, in Monte Stella «diventa un polittico che si articola attraverso cinque sezioni». Il termine “polittico” richiama la pittura, ma potremmo aggiungere ancora un riferimento alla musica definendo le composizioni di Monte Stella “polifoniche”, tra «intrecci fra il presente, il passato e qualche proiezione del futuro; una sorta di andirivieni del pensiero che rivisita alcuni luoghi del salernitano, del nostro Mezzogiorno, di Roma, di New York e della Provenza, ma anche con riferimenti a personaggi della mia famiglia o ad alcuni compagni della mia giovinezza, fino all’esperienza assiale della paternità e, per riflesso, quella relativa ai miei Lari».

Una caratteristica fondamentale di Monte Stella è la scelta di non chiudere, di non prospettare neppure per un istante, pur nella cognizione del tempo e del dolore, una linea orizzontale che ponga termine alla sequenza delle cose e degli eventi, dei sensi e dei sentimenti.

Fontanella è consapevole di ogni strappo, di ogni ferita, al giusto, al bello, all’essenza stessa dell’umanità. Ma il suo pessimismo è fronteggiato sempre, e regolarmente sconfitto, o almeno placato, mutato di volto e di segno, da una vitalità, nel senso stretto e metaforico del termine, che non si esaurisce e non si placa. Molte sono le poesie del libro che confermano questa tendenza. Un esempio, lineare e forte, è quello della lirica di pagina 74 dedicata alla figlia Emma: «Una sola certezza, una piccola figlia / ora già donna». Con un finale mirabile nella sua immediatezza: “Non scordarti mai che tu mi sei figlia». Per creare il cerchio di cui si è detto, quello che contrasta il tempo e la morte, non servono materiali complessi, servono materiali saldi. E il verso citato ne è un valido esempio.

Sono le radici ed i rami, e la possibilità di essere allo stesso tempo gli uni e gli altri, a combattere la tentazione della resa. Oltre ai Lari, e oltre ai figli, ci sono i luoghi, quelli reali e quelli mitici, e anche in questo caso confonderli, nella mente e nel cuore, contribuisce a rinforzare la barriera difensiva.

Monte Stella è un libro di memorie, un diario di viaggio, ma anche, in fondo, un autoritratto. Il ritratto di una “verde senescenza” ma anche quello di un pessimista tenacemente appassionato e saldamente avvinto alla vita. Un poeta che registra con il magnetofono versi onirici che sono assolutamente reali e ricordi reali che sono assolutamente onirici. In una raccolta di poesie che parla di distacco ma che ancora ricerca «il Senso, se senso esiste, che regola la vita». E, a dispetto di tutto, spera e crede che la poesia «possa giocare un ruolo di miglioramento etico-sociale della nostra esistenza, minata continuamente da sciagure, ingiustizie, soprusi».

Questo libro ci conferma che, anche se siamo conchiglie dimenticate nel vento, possiamo «aspettare un’alba – come sempre». Ci dice, anzi ci racconta, del «vento che non smette di / soffiarti sulla faccia», ma anche di quella parte insondabile, magica, che vale comunque la pena di annotare, ascoltare e rivivere: quel «bambino che dorme / disegnando nell’aria il suo nudo / mistero».

Ivano Mugnaini